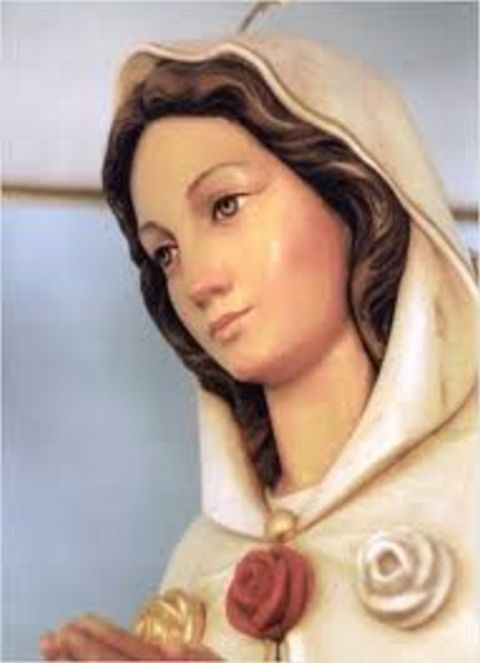

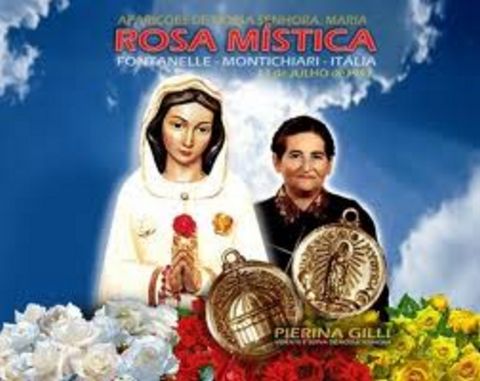

The history of the image begins with the sculptor, Amilcare Santini, who modeled it in three days “under artistic inspiration.” It was made of plaster dissolved in water and poured into a mold and turned out to dry in the sun. It was then sprayed with a varnish to render it suitable for painting. After it was colored, varnished and polished, ordinary screws were used to attach the image to a panel of black opaline. The panel measures 39 by 33 centimeters, the figure 29 by 22 centimeters. The plaque was mass-produced in Tuscany, Italy and then shipped to Syracuse for retail.

The plaque was purchased a s a wedding gift for Antonina and Angelo Iannuso, who were married on March 21, 1953. They admitted that they were tepid and neglectful Christians, yet they hung the image with some devotion on the wall behind their bed. Angelo was a laborer who had taken his bride to live in the home of his brother on Via Degli Orti 11. When his wife discovered that she was pregnant, her condition was accompanied by toxemia that expressed itself in convulsions that at times brought on temporary blindness.

At three in the morning on Saturday, August 29, 1953, Antonina suffered a seizure that left her blind. At about 8:30 a.m. that morning, her sight was miraculously restored. When she was able to see, her eyes were on the Madonna, which, to Antonina’s amazement was weeping effusive tears. In her own words, Antonina reports:

“I opened my eyes and stared at the image of the Madonna above the bedhead. To my great amazement, I saw that the effigy was weeping. I called my sister-in-law Grazie and my aunt, Antonian Sgarlata, who came to my side, showing them the tears. At first they thought it was a hallucination due to my illness, but when I insisted, they went close up to the plaque and could well see that tears were really falling from the eyes of the Madonna, and that some tears ran down her cheeks onto the bedhead. Taken by fright they took it out the front door, calling the neighbors, and they too confirmed the phenomenon…”

The weeping was not continual, but happened about six or seven times that morning, and also again in the evening, when the husband had returned home. By now it was apparent that Antonina’s illness, which had puzzled her doctors, was cured, and all this led to the conversion of the couple, and many others. Over the next two days the weeping continued at intervals, and were witnessed by thousands of people, even when the plaque was moved from the bedroom to a little altar outside the house.

One of the many visitors who examined the plaque at close range was Mario Messina, who was highly regarded in the neighborhood. After observing the slow formation of the tears, he removed the image from the wall, looked at it thoroughly, and was satisfied that the tears were not the result of an internal reservoir. After the plaque was dried, two tears immediately reappeared.

News of the phenomenon spread rapidly throughout the city, bringing crowds that forced their way indoors and gathered in the streets around the house. The security inspector, with the couple’s permission, hung the plaque on the outside of the house to satisfy the curiosity of the people. Later, seeing that the crowds showed no sign of diminishing, the picture was taken to the constabulary (police) in an effort to reduce the confusion. The image wept while outside the building and during its transport, but, after 40 minutes at the police station where it did not weep, it was returned to the Iannuso home.

On Sunday, August 30 at 2:00 in the morning, the weeping image was placed on a cushion and displayed for the curious who had remained in the street throughout the night. The plaque was nailed above the main door on Monday, and its tears were collected by the people on pieces of cloth and wads of cotton. During this time skeptics became convinced, and many of the sick were healed. That same Monday, to protect the plaque from falling, it was brought to an improvised altar outside the home of the Lucca family who lived across the street. After the recitation of the Rosary, it was returned.

Three priests visited the home during this time, one of whom notified the chancery. It assembled a group of clergy, four of scientific background and three for reputable witnesses, to comprise an investigating commission. On the specific instructions of the chancellor, the group met at the Iannuso home on Tuesday, Sept. 1 to study the phenomenon, collecting a sample of tears for analysis. The plaque was examined while it wept and while the liquid collected in the cavity formed by the hand over the heart. The commission examined the smooth finish and found no pores or irregularities on the surface. The backing was removed and the unfinished gypsum was scrutinized and found to be dry, even though tears collected on the reverse. Six coats of nitrocellulose colors were counted on the image; these were covered with varnish. Using a sterilized pipette, a sample of tears was collected, placed in a sterile vial, and taken to the provincial laboratory to be examined by doctors and chemists.

Following this through investigation, the image continued weeping for another 51 minutes, but at 11:40 in the morning the tears stopped, never to begin again. The sample of tears was scientifically compared to tears from an adult and a child. Following a detailed analysis, the doctors reached this conclusion:

“The liquid examined is shown to be made up of a watery solution of sodium chloride in which traces of protein and nuclei of a silver composition of excretory substances of the quaternary type, the same as found in the human secretions used as a comparison during the analysis. The appearance, the alkalinity and the composition induce one to consider that the liquid examined is analogous to human tears.”

The report was dated September 9, 1953 and signed by the examining doctors, Drs. Michele Cassola, Francesco Cotzie, Leopoldo La Rosa and Mario Marietta. The facts of the case were sent to Rome on September 10, to Cardinal Pizzardo, secretary of the Holy Office.

Miraculous cures were claimed and crowds of faithful gathered in the town. The local archbishop arrived the next day to make inquiries and to speak to witnesses. As reports of miraculous healings began to spread, there was the formation of a medical commission. Archbishop Baranzini returned on September 8 with other ecclesiastics to say the rosary, and to explain to the crowd the meaning of these tears. He said that they were tears of sorrow and distress, a sign to a society and culture which had gone astray.

Archbishop Baranzini returned on September 19, to preach again to the growing crowds, telling them that these were the tears of a mother, weeping because of the persecutions her children were suffering in the East, and because of the loss of faith in the West. During September and October over a million pilgrims visited the plaster figure of Mary, which had been moved to a more prominent location.

Archbishop Baranzini went to Rome on September 24, and met Pope Pius XII on September 27. In December of 1953, the bishops of Sicily met to pass official judgement, and their leader, Cardinal Ruffini, explained their positive decision in the following statement:

“The bishops of Sicily, gathered together for their regular conference at Palermo, have heard the full report by His Excellency, Archbishop Ettore Baranzini of Syracuse, on the weeping of an image of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Having weighed carefully all the related evidence contained in the original documents, the bishops have unanimously judged that the reality of the weeping cannot be held in doubt. We express the desire that such a manifestation of the Heavenly Mother may inspire all to salutary penance and to a livelier devotion towards the Immaculate Heart of Mary and that there may be the prompt construction of a sanctuary to perpetuate the memory of the miracle.”

On October 17, 1954, Pope Pius XII stated the following during a radio broadcast:

“We acknowledge the unanimous declaration of the Episcopal Conference held in Sicily on the reality of that event. Will men understand the mysterious language of those tears?”

The medical commission that was nominated on October 7, 1953 to seriously and scientifically examine the nature of extraordinary cures (worked through the intercession of the Weeping Madonna of Syracuse) considered 290 cases of which 105 were of “special interest.” These miracles were reported within a few years of the incident.

The first person to experience a miracle of healing was also the first to observe the weeping. From the time Antonina Iannuso first saw the tears, she recovered completely from severe toxemia and gave birth to a healthy son on December 25, 1953. Archbishop Baranzini officiated at the infant’s Baptism.

The same astonishment experienced by the people of Syracuse at the time of the miracle was felt by those around the world who read about the occurrence in local newspapers or heard about it on radio or television. It has been tabulated that reports even reached India, China, Japan and Vietnam. In Italy alone more than 2,000 articles appeared in 225 papers and magazines, while hundreds of articles appeared in 93 foreign newspapers in 21 different nations. Rarely is an event of religious interest given such worldwide attention.

The question of condensation is likewise rejected since it would have covered the whole statue and would not have originated only from the corners of the eyes. Condensation would have collected on nearby objects as well, which did not occur, and, if it had been present, it certainly would not have been salty. The physicians and scientists who studied the event could offer no natural explanation for the occurrence and deemed it extraordinary in several documents.

The reliquary presented to Archbishop Baranzini on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his ordination is of special interest since it contains the tears collected by the medical commission for their chemical analysis. The reliquary is comprised of three layers. The bottom contains, in addition to cloths that had been saturated with tears, one of the vials that contained the tears collected by the commission and cotton wool that absorbed some of the tears on another occasion. The second layer has four panels depicting the events. The third and highest layer has a crystal urn which holds another of the vials used for the collection of the samples. The tears within it are now crystallized.

The little house on Via Degli Orti 11, where the Madonna first shed her tears, is now an oratory where Mass is often celebrated. The image itself is enshrined above the main altar of the Santuario Madonna Delle Lacrima, built specifically to accommodate the crowds that continually gather in prayer before the holy image.